Baby boomers

| Part of a series on |

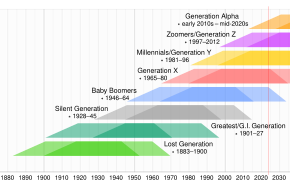

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (November 2024) |

Baby boomers, often shortened to boomers, are the demographic cohort preceded by the Silent Generation and followed by Generation X. The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964 during the mid-20th century baby boom. The dates, the demographic context, and the cultural identifiers may vary by country.[1][2][3][4] Most baby boomers are the children of either the Greatest Generation or the Silent Generation, and are often the parents of the younger members of Generation X and Millennials.[5] In the West, boomers' childhoods in the 1950s and 1960s had significant reforms in education, both as part of the ideological confrontation that was the Cold War,[6][7] and as a continuation of the interwar period.[8][9] Theirs was a time of economic prosperity and rapid technological progress.[10] In the 1960s and 1970s, as this relatively large number of young people entered their teens and young adulthood—the oldest turned 18 in 1964, the youngest in 1982—they, and those around them, created a very specific rhetoric around their cohort,[11] and the social movements brought about by their size in numbers, such as the counterculture of the 1960s[12] and its backlash.[13]

In many countries, this period was one of deep political instability due to the postwar youth bulge.[13][14] In China, boomers lived through the Cultural Revolution and were subject to the one-child policy as adults.[15] These social changes and rhetoric had an important impact in the perceptions of the boomers, as well as society's increasingly common tendency to define the world in terms of generations, which was a relatively new phenomenon. This group reached puberty and maximum height earlier than previous generations.[16]

In Europe and North America, many boomers came of age in a time of increasing affluence and widespread government subsidies in postwar housing and education,[17] and grew up genuinely expecting the world to improve with time.[18] Those with higher standards of living and educational levels were often the most demanding of betterment.[13][19] In the early 21st century, baby boomers in some developed countries are the single biggest cohort in their societies due to sub-replacement fertility and population aging.[20] In the United States, they are the second most numerous age demographic after millennials.[21]

Etymology

[edit]The term baby boom refers to a noticeable increase in the birth rate. The post-World War II population increase was described as a "boom" by various newspaper reporters, including Sylvia F. Porter in a column in the May 4, 1951, edition of the New York Post, based on the increase of 2,357,000 in the population of the U.S. from 1940 to 1950.[22]

The first recorded use of "baby boomer" is in a January 1963 Daily Press article by Leslie J. Nason describing a massive surge of college enrollments approaching as the oldest boomers were coming of age.[23][24] The Oxford English Dictionary dates the modern meaning of the term to a January 23, 1970, article in The Washington Post.[25]

Date range and definitions

[edit]A significant degree of consensus exists around the date range of the baby boomer cohort, with the generation considered to cover those born from 1946 to 1964 by various organizations such as the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary,[27] Pew Research Center,[28] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,[29][30] Federal Reserve Board,[31] Australian Bureau of Statistics,[32] Gallup,[33] YouGov[34] and Australia's Social Research Center.[35] The United States Census Bureau defines baby boomers as "individuals born in the United States between mid-1946 and mid-1964".[36][37] Landon Jones, in his book Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation (1980), defined the span of the baby-boom generation as extending from 1946 through 1964.[38]

Others have delimited the baby boom period differently. Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe, in their 1991 book Generations, define the social generation of boomers as that cohort born from 1943 to 1960, who were too young to have any personal memory of World War II, but old enough to remember the postwar American High before John F. Kennedy's assassination.[39]

David Foot, author of Boom, Bust and Echo: Profiting from the Demographic Shift in the 21st Century (1997), defined a Canadian boomer as someone born from 1947 to 1966, the years in which more than 400,000 babies were born. He acknowledges, though, that this is a demographic definition, and that culturally, it may not be as clear-cut.[40] Doug Owram argues that the Canadian boom took place from 1946 to 1962, but that culturally, boomers everywhere were born between the late war years and about 1955 or 1956. Those born in the 1960s might feel disconnected from the cultural identifiers of the earlier boomers.[41]

French sociologist Michèle Delaunay in her book Le Fabuleux Destin des Baby-Boomers (2019), places the baby-boom generation in France between 1946 and 1973, and in Spain between 1958 and 1975.[4] Another French academic, Jean-François Sirinelli, in an earlier study, Les Baby-Boomers: Une génération 1945-1969 (2007) denotes the generation span between 1945 and 1969.[42]

The Office for National Statistics has described the UK as having had two baby booms in the middle of the 20th century, one in the years immediately after World War II and one around the 1960s with a noticeably lower birth rate (but still significantly higher than that seen in the 1930s or later in the '70s) during part of the 1950s.[45] Bernard Salt places the Australian baby boom between 1946 and 1961.[3][46]

In the US, the generation can be segmented into two broadly defined cohorts: the "leading-edge baby boomers" are individuals born between 1946 and 1955, those who came of age during the Vietnam War and Civil Rights eras.[47] This group represents slightly more than half of the generation, or roughly 38,002,000 people. The other half of the generation, usually called "Generation Jones", but sometimes also called names like the "late boomers" or "trailing-edge baby boomers", was born between 1956 and 1964, and came of age after Vietnam and the Watergate scandal.[47][48][49][50][51] This second cohort includes about 37,818,000 people.[52] Others use the term Generation Jones to refer to a cusp generation, which includes those born in the latter half of the Baby Boomers to the early years of Generation X, with a typical range of 1954 to 1965.[53][54][55]

Demographics

[edit]Asia

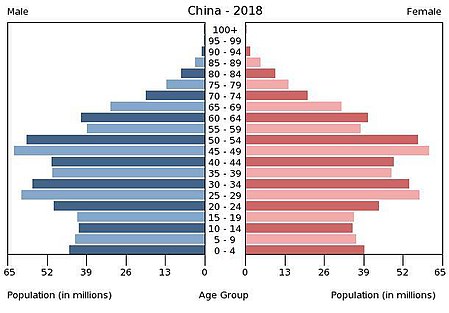

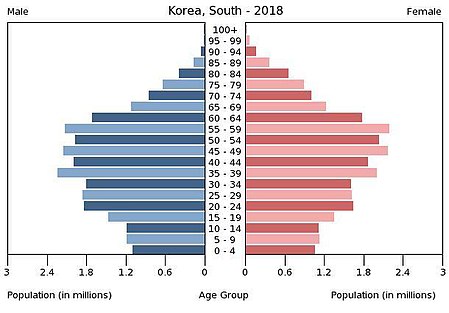

[edit]- Population pyramids of China, Japan, and South Korea in 2018

During the time of the Great Leap Forward, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) encouraged couples to have as many children as possible because it believed a growing labor force was needed for national development along socialist lines.[56] China's baby-boom cohort is the largest in the world. According to journalist and photographer Howard French, who spent many years in China, many Chinese neighborhoods were, by the mid-2010s, disproportionately filled with the elderly, to whom the Chinese themselves referred as a "lost generation", who grew up during the Cultural Revolution, when higher education was discouraged and large numbers of people were sent to the countryside for political reasons. As China's baby boomers retire in the late-2010s and onward, the people replacing in the workforce will be a much smaller cohort due to the one-child policy. Consequently, China's central government faces a stark economic trade-off between "cane and butter"—how much to spend on social welfare programs such as state pensions to support the elderly and how much to spend in the military to achieve the nation's geopolitical objectives.[15]

According to the National Development Council of Taiwan, the nation's population could start shrinking by 2022 and the number of people of working age could fall 10% by 2027. About half of Taiwanese would be aged 50 or over by 2034.[57] At the current rate, Taiwan is set to transition from an aged to super-aged society, where 21% of the population is over 65 years of age, in eight years, compared to seven years for Singapore, eight years for South Korea, 11 years for Japan, 14 for the United States, 29 for France, and 51 for the United Kingdom.[58]

Japan at present has one of the oldest populations in the world and persistently subreplacement fertility, currently 1.4 per woman. Japan's population peaked in 2017. Forecasts suggest that the elderly will make up 35% of Japan's population by 2040.[59] As of 2018, Japan was already a super-aged society,[60] with 27% of its people being older than 65 years.[61] According to government data, Japan's total fertility rate was 1.43 in 2017.[62] According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Japan has one of the oldest populations in the world, with a median age of 47 years in 2017.[63]

A baby boom occurred in the aftermath of the Korean War, and the government subsequently encouraged people to have no more than two children per couple. Although South Korean fertility remained above replacement well in to the 1970s,[64] its fertility has since been declining due to declining economic prospects for young people, and women's liberation. In recent times, the South Korean government has since made many efforts to increase the national fertility rate through subsidies; however, these efforts have failed, and South Korea retains one of the world's lowest fertility rates, with a total fertility rate of less than 1 child per woman.[65]

Europe

[edit]-

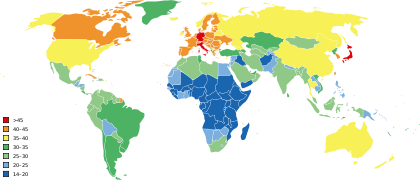

European countries by proportions of people aged 65 and over in 2018

-

Population pyramid of the European Union in 2016

From about 1750 to 1950, Western Europe transitioned from having both high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates. By the late 1960s or 1970s, the average woman had fewer than two children, and although demographers at first expected a "correction", such a rebound never came. Despite a bump in the total fertility rates of some European countries in the very late 20th century (the 1980s and 1990s), especially France and Scandinavia, they never returned to replacement level; the bump was largely due to older women realizing their dreams of motherhood. Member states of the European Economic Community saw a steady increase in not just divorce and out-of-wedlock births between 1960 and 1985 but also falling fertility rates. In 1981, a survey of countries across the industrialized world found that while more than half of people aged 65 and over thought that women needed children to be fulfilled, only 35% of those between the ages of 15 and 24 (younger baby boomers and older generation Xers) agreed. Falling fertility was due to urbanization and decreased infant mortality rates, which diminished the benefits and increased the costs of raising children. In other words, investing more in fewer children became more economically sensible, as economist Gary Becker argued. (This is the first demographic transition.) By the 1960s, people began moving from traditional and communal values towards more expressive and individualistic outlooks due to access to and aspiration of higher education, and to the spread of lifestyle values once practiced only by a tiny minority of cultural elites. (This is the second demographic transition.)[66]

At the start of the 21st century, Europe has an aging population. This problem is especially acute in Eastern Europe, whereas in Western Europe, it is alleviated by international immigration.[67] Researches by demographers and political scientists Eric Kaufmann, Roger Eatwell, and Matthew Goodwin suggest that such immigration-induced ethnodemographic change is one of the key reasons behind public backlash in the form of national populism across the rich liberal democracies, an example of which is the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum (Brexit).[68]

In 2018, 19.70% of the population of the European Union (EU) were 65 or older.[61] The median age was 43 in 2019, and was about 29 in the 1950s. Europe had significant population growth in the late 20th century. However, Europe's growth is projected to halt by the early 2020s due to falling fertility rates and an aging population. In 2015, a woman living in the EU had on average 1.5 children, down from 2.6 in 1960. Although the EU continues to experience a net influx of immigrants, this is not enough to balance out the low fertility rates.[69] In 2017, the median age was 53.1 years in Monaco, 45 in Germany and Italy, and 43 in Greece, Bulgaria, and Portugal, making them some of the oldest countries in the world besides Japan and Bermuda. They are followed by Austria, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Spain, whose median age was 43.[63]

North America

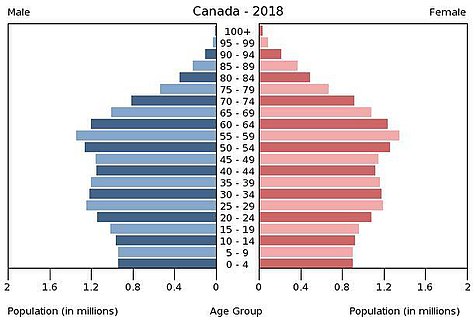

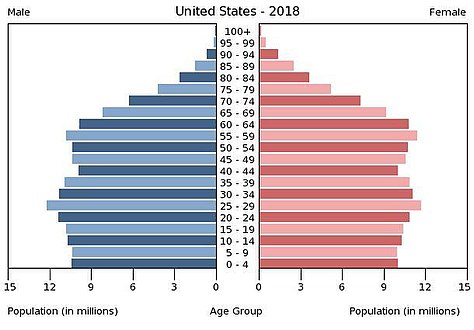

[edit]- Population pyramids of Canada and the United States

By the mid-2010s, sub-replacement fertility and growing life expectancy meant that Canada had an aging population.[70] Statistics Canada reported in 2015 that for the first time in Canadian history, more people were aged 65 and over than people below the age of 15. One in six Canadians was above the age of 65 in July 2015.[71] Projections by Statistics Canada suggest this gap will only increase in the next 40 years. Economist and demographer David Foot from the University of Toronto told CBC that policymakers have ignored this trend for decades. With the massive baby-boom generation entering retirement, economic growth will be slower and demand for social support will rise. This will significantly alter the Canadian economy. Nevertheless, Canada remained the second-youngest G7 nation, as of 2015.[70]

Historically, the early Anglo-Protestant settlers in the 17th century were the most successful group, culturally, militarily, economically, and politically, and they maintained their dominance until the early 20th century. Commitment to the ideals of the Enlightenment meant that they sought to assimilate newcomers from outside of the British Isles, but few were interested in adopting a pan-European identity for the nation, much less turning it into a global melting pot, but in the early 1900s, liberal progressives and modernists began promoting more inclusive ideals for what the national identity of the United States should be. While the more traditionalist segments of society continued to maintain their Anglo-Protestant ethnocultural traditions, universalism and cosmopolitanism started gaining favor among the elites. These ideals became institutionalized after the Second World War, and ethnic minorities started moving towards institutional parity with the once-dominant Anglo-Protestants.[72] The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart–Celler Act), passed at the urging of President Lyndon B. Johnson, abolished national quotas for immigrants, and replaced it with a system that admits a fixed number of persons per year based in qualities such as skills and the need for refuge. Immigration subsequently surged from elsewhere in North America (especially Canada and Mexico), Asia, Central America, and the West Indies.[73] By the mid-1980s, most immigrants originated from Asia and Latin America. Some were refugees from Vietnam, Cuba, Haiti, and other parts of the Americas, while others came illegally by crossing the long and largely undefended U.S.-Mexican border. Although Congress offered amnesty to "undocumented immigrants" who had been in the country for a long time and attempted to penalize employers who recruited them, their influx continued. At the same time, the postwar baby boom and subsequently falling fertility rate seemed to jeopardize America's Social Security system as the baby boomers retire in the early 21st century.[74]

Using their own definition of baby boomers as people born between 1946 and 1964 and U.S. census data, the Pew Research Center estimated 71.6 million boomers were in the United States as of 2019.[75] The age wave theory suggests an economic slowdown when the boomers started retiring during 2007–2009.[76] In 2018, though, 29% of people aged 65–72 in the United States remained active in the labor force, according to the Pew Research Center. This trend follows from the general expectation of Americans to work after the age of 65. The baby boomers who chose to remain in the work force after the age of 65 tended to be university graduates, whites, and residents of the big cities. That the boomers maintained a relatively high labor participation rate made economic sense because the longer they postpone retirement, the more Social Security benefits they could claim, once they finally retire.[77]

As adolescents and young adults

[edit]Standards of living and economic prospects

[edit]After the Second World War, the United States offered massive financial assistance to Western European nations in the form of the Marshall Plan to rebuild themselves and to extend U.S. economic and political influence. The Soviet Union did the same for Eastern Europe with the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance. Western Europe had considerable economic growth, due to both the Marshall Plan and initiatives aimed at European integration, starting with the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community by France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg in 1951 and the European Community in 1957–58.[79][20] As a matter of fact, the Anglo-Americans spoke of the 'Golden Age' and French of '30 glorious years' (les trente glorieuses) continued economic growth. For the United States, the postwar economic expansion was a continuation of what had occurred during the war, but for Western Europe and Japan, the primary economic goal was to return to prewar levels of productivity and prosperity, and many managed to close the gap with the United States in productivity per work hour and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Full employment was reached on both sides of the Atlantic by the 1960s. In Western Europe, the average unemployment figure stood at 1.5% at that time. The automobile, already a common sight in North America, became so in Western Europe, and to a lesser extent, Eastern Europe and Latin America. At the same time, governments around the world undertook the construction or expansion of public transportation networks at a rate never before seen.[80]

Many items previously deemed luxurious, such as the laundry machine, the dishwasher, the refrigerator, and the telephone, entered mass production for the average consumer. The average person could live like the upper class in the previous generation. Technological advances made before, during, and after the war, such as plastics, television, magnetic tape, transistors, integrated circuits, and lasers, played a key role in the tremendous improvements in the standards of living for the average citizen in the developed world.[80][81] This was a time of optimism, economic prosperity, and a growing middle class.[10] In some instances, the rate of technological change was so rapid even when compared to optimistic projections, so much so that some social theorists of the day warned of boredom for the housewife.[81] In reality, it paved the way for a more individualistic culture and women's emancipation, something the Baby Boomers would push for when they came of age during the late 1960s and 1970s. It was also one of the reasons why the baby boom lasted for as long as it did; housekeeping and child-rearing became less onerous for women.[10] Nevertheless, after 1945, because child labor had been virtually eradicated in the West, married women from families of modest means had to join the work force.[19] As Louise Tilly and Joan Scott explain, "in the past children had worked so that their mothers could remain at home fulfilling domestic and reproductive responsibilities. Now when families needed additional income, mothers worked instead of children."[82]

Demand for housing exploded. Governments both in the East and the West massively subsidized housing with many public housing projects in urban areas in the form of high-rise apartment buildings. In many cases, this came at the cost of destroying historical sites.[80] As standards of living continued to climb, decentralization took root, and suburban communities began developing their own entertainment quarters and shopping malls.[19]

Public health improved, too, with vaccination programs playing an important role. In the United Kingdom, for example, the introduction of vaccines against poliomyelitis, measles, and pertussis (whooping cough) in the 1950s and 1960s caused infection rates to plummet, albeit with some upticks due to vaccine hesitancy.[83] In the United States, vaccination against measles resulted in not only falling childhood mortality rates but also other positive life outcomes such as rising family income.[84] In the West, average life expectancy increased by about seven years between the 1930s and 1960s.[80]

Prosperity was taken for granted. Indeed, for many young people who came of age after 1945, the interwar experience of mass unemployment and stable or falling prices was confined to the history books. Full employment and inflation were the norm.[80] The new-found wealth allowed many Western governments to finance generous welfare programs. By the 1970s, all industrialized capitalist nations had become welfare states. Six of them—Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, West Germany, and Italy—spent more than 60% of their national budgets on welfare. When the 'Golden Age' came to an end, such government largess proved problematic.[80]

In fact, the 'Golden Age' finally petered out in the 1970s,[20] as automation started eating away jobs at the low to medium skill levels,[19] and as the first waves of people born after the Second World War entered the workplace en masse.[85] In the United States, at least, the onset of a recession—as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research—typically occurred within a few years of a peak in the rate of change of the young-adult population, both positive and negative, and indeed, the recession of the early 1970s took place shortly after the growth of people in their early 20s peaked in the late 1960s.[85] Western capitalist nations slid into recessions during the mid-1970s and the early 1980s. Although the collective GDP of these nations continued to grow until the early 1990s, so much so that they became much wealthier and more productive by that date, unemployment, especially youth unemployment, exploded in many industrialized countries. In the European Community, the average unemployment rate stood at 9.2% by the late 1980s, despite the deceleration of population growth. Youth unemployment during the 1980s was over 20% in the United Kingdom, more than 40% in Spain, and around 46% in Norway. Generous welfare programs alleviated the potential of social unrest, though Western governments found themselves squeezed by a combination of falling tax revenue and high state spending.[86] People born during the baby bust due to the Great Depression in the 1930s found themselves in an abundance of employment opportunities as they entered the workforce in the 1950s. In fact, they could expect to achieve parity with their fathers' wages at the entrance level. This, however, was not the case for the postwar generation. By the mid-1980s, people could only expect to make a third of what their fathers made as new entrants to the labor force.[85]

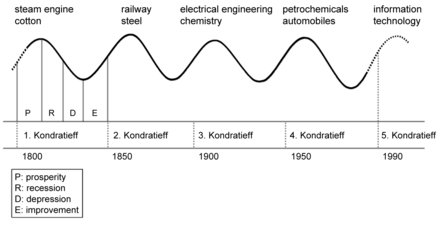

The pace of economic growth in the 1960s was understood to be unprecedented. In the long-term view, though, it was just another upswing in the Kondratiev cycle (see figure), much like the mid-Victorian boom or the Belle Époque from around 1850 to 1873 in Britain and France, respectively. Globally, agricultural output doubled between the early 1950s and early 1980s—more than that in North America, Western Europe, and East Asia—while the fishing industry tripled its catches.[80]

Communist nations, especially the Soviet Union and the Eastern European states, grew considerably, too. Heretofore agrarian states such as Bulgaria and Romania began to industrialize. By the 1960s, though, the growth of the communist states faltered compared to the capitalist industrialized countries.[80] By the 1980s, the economies of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe became stagnant. This was, however, not the case in the newly industrializing economies such as China or South Korea, whose process of industrialization began much later, nor was it in Japan.[86]

The developing world achieved significant growth during the 1950s and 1960s, though it never quite reached the level of affluence of industrialized societies. The populations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America boomed between 1950 and 1975. Food production comfortably outpaced population growth. As a consequence, this period saw no major famines other than cases due to armed conflict and politics, which did happen in Communist China.[80] People who experienced the Great Famine of China (1958–1961) as toddlers were noticeably shorter than those who did not. The Great Famine killed up to 30 million people and massively reduced China's economic output.[87] But before the Famine, China's agricultural output increased 70% from the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 to 1956, according to official statistics. Chairman Mao Zedong introduced a plan for the rapid industrialization of his country, the Great Leap Forward. Steel production, mainly from flimsy household furnaces, tripled between 1958 and 1960, but fell to a level lower than that at the start of the Great Leap Forward by 1962. Rural life—China was a predominantly rural society at this point in history—including family affairs, was collectivized. Women were recruited to the workplace, that is, the fields, while the government provided them with nursery and childcare services. In general, monetary income was replaced by six basic services: food, healthcare, education, haircuts, funerals, and movies. Mao's plan was quickly abandoned, not just because it failed, but also because of the Great Famine. Yet despite the disastrous results of Maoist policies, by the standards of the developing world, China was not doing so poorly. By the mid-1970s, China's food consumption measured in calories was just above the global median and the nation's life expectancy grew steadily, interrupted only by the famine years.[88]

Between 1960 and 1975, the Chinese mainland's growth was fast, but lagged behind the growth of Japan and the rise of the Four Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) grew even faster.[88]

Education

[edit]Universal literacy was a major goal for practically all governments in the developing world and many made significant progress towards this end, even if their 'official' statistics were questionably optimistic.[19] In the 1980s, James R. Flynn examined psychometric data and discovered evidence that the IQ scores of Americans were increasing significantly between the early 1930s and late 1970s. On average, younger cohorts scored higher than their elders. This was confirmed by later studies and on data in other countries; the discovery became known as the Flynn effect.[89]

During the postwar era, the importance of modern mathematics—especially mathematical logic, optimization, and numerical analysis—was acknowledged for its usefulness during the war. From this sprang proposals for reforms in mathematics education. The international movement to bring about such reforms was launched in the late 1950s, with heavy French influence. In France, they also grew out of a desire to bring the subject as it was taught in schools closer to the research done by pure mathematicians, particularly the Nicholas Bourbaki school, which emphasized an austere and abstract style of doing mathematics, axiomatization.[note 1] Up until the 1950s, the purpose of primary education was to prepare students for life and future careers. This changed in the 1960s. A commission headed by André Lichnerowicz was established to work out the details of the desired reforms in mathematics education. At the same time, the French government mandated that the same courses be taught to all schoolchildren, regardless of their career prospects and aspirations. Thus the same highly abstract courses in mathematics were taught to not just those willing and able to pursue university studies but also those who left school early to join the workforce. From elementary school to the French Baccalaureate, Euclidean geometry and calculus were de-emphasized in favor of set theory and abstract algebra. This conception of mass public education was inherited from the interwar period and was taken for granted; the model for the elites was to be applied to all segments of society. But by the early 1970s, the Commission ran into problems. Mathematicians, physicists, members of professional societies, economists, and industrial leaders criticized the reforms as being suitable for neither schoolteachers nor students. Many teachers were ill-prepared and ill-equipped. One member of the Lichnerowicz Commission asked, "Should we teach outdated mathematics to less intelligent children?" Lichnerowicz resigned and the commission was disbanded in 1973.[9] In the United States, the "New Math" initiative—under which students received lessons in set theory, which is what mathematicians actually use to construct the set of real numbers, something advanced undergraduates learned in a course on real analysis,[note 2] and arithmetic with bases other than ten[note 3]—was similarly unsuccessful,[7] and was widely criticized by not just parents,[7] but also STEM experts.[90][91][92] Nevertheless, the influence of the Bourbaki school in mathematics education lived on, as the Soviet mathematician Vladimir Arnold recalled in a 1995 interview.[93]

Before World War II, the share of university-educated people in even the most advanced of industrialized nations, except the United States, a world leader in post-secondary education, was negligible. After the war, the number of university students skyrocketed, not just in the West, but also among developing countries as well. In Europe, between 1960 and 1980, the number of university students increased by a factor of four to five in West Germany, Ireland, and Greece, a factor of five to seven in Finland, Iceland, Sweden and Italy, and a factor of seven to nine in Spain and Norway.[19] In West Germany, the number of university students steadily grew in the 1960s despite the construction of the Berlin Wall, which prevented East German students from coming. By 1966, West Germany had a grand total of 400,000 students, up from 290,000 in 1960.[94] In the Republic of Korea (South Korea), the number of university students as a share of the population grew from around 0.8% to 3% between 1975 and 1983. Families typically considered higher education to be the gateway towards a higher social status and higher income, or, in short, a better life; as such they pushed their children to university whenever possible. In general, the postwar economic expansion made it possible for a larger percentage of the population to send their children to university as full-time students. Moreover, many Western welfare states, starting with U.S. government subsidies to military veterans who wished to attend university, provided financial aid in one form or another to university students, though they were still expected to live frugally. In most countries, with the notable exceptions of Japan and the U.S., universities were more likely to be public rather than private. The total number of universities worldwide more than doubled in the 1970s. The rise of university campuses and university towns was a culturally and politically novel phenomenon, and one that would usher in the political turbulence of the late 1960s around the world.[19]

After World War I, the goal of primary education in the United States shifted from using schools to realize social change to employing them to promote emotional development. While it might have helped students improve their mental welfare, critics pointed to the de-emphasizing of traditional academic subjects leading to poor work habits and plain ignorance. Such a system became less and less tenable because society increasingly demanded rigorous education. In his book The American High School Today (1959), former Harvard president James B. Conant laid out his critique of the status quo. In particular, he pointed to the failure of English classes in teaching proper grammar and composition, the neglect of foreign languages, and the inability to meet the needs of gifted and slow students alike. People like Conant rose to prominence due to the successful launch of the Sputnik satellite by the Soviet Union in 1957.[8] As a matter of fact, the passages of the artificial satellite were recorded by the Boston newspapers and viewed with the naked eye from rooftops.[6]

This surprising Soviet success demonstrated to the Americans that their education system had fallen behind.[7] Life magazine reported that three quarters of American high-school students took no physics at all. The U.S. government realized it needed thousands of scientists and engineers to match the might of its ideological rival. On President Dwight D. Eisenhower's direct orders, science education underwent major reforms and the federal government started pouring enormous sums of money into not just education but also research and development. Private institutions, such as the Carnegie Corporation and the Ford Foundation provided funding for education, too.[8][95] Authors felt inspired to cater to the physics textbook market, and one of the results was the Berkeley Physics Course, a series for undergraduates influenced by MIT's Physical Science Study Committee, formed right before the launch of Sputnik. One of the most famous of textbooks from the Berkeley series is Electricity and Magnetism by Nobel laureate Edward Mills Purcell, which has gone through multiple editions and remains in print in the twenty-first century.[6]

In any case, academic performance reclaimed its importance in the United States. At the same time, large numbers of young people desired to go to college due to population growth and the needs of society for specialized skills. Prestigious institutions were able to handpick the very best of students from massive pools of applications and consequently became the training centers for a growing class of cognitive elites. Indeed, the share of college graduates among 23-year-olds steadily rose after World War II, first due to veterans returning to civilian life and later due to people born after the war. In 1950, there were 2.6 million students in American institutions of higher learning. By 1970, that number was 8.6 million, and by 1980, it became 12 million.[8] In the 1970s, there was a seemingly infinite number of Baby Boomers applying for admissions at institutions of higher learning in the U.S., so much so that many schools became extremely difficult to get into. This cooled off by the 1980s, though.[96] In the end, about a quarter of Baby Boomers had at least a bachelor's degree.[97] More women earned university degrees than ever before, and became professionals at an unprecedented rate.[98] Because so many Baby Boomers pursued higher education, costs started to rise, making the Silent Generation was the last cohort to benefit from tuition-free public universities anywhere in the United States.[10] The number of women pursuing higher education grew in other countries, too, including those on the other side of the Iron Curtain.[19]

American physicist Herbert Callen observed that even though a survey conducted by the American Physical Society Committee on the Applications of Physics reported (in the Bulletin of the APS) in 1971 that industry leaders desired a greater emphasis on more practical subjects, such as thermodynamics as opposed to the more abstract statistical mechanics, academia subsequently went the other way.[99] British physicist Paul Dirac, who had relocated to the United States in the 1970s, opined to his colleagues he doubted the wisdom of educating so many undergraduates in science when so many of them had neither the interest nor the aptitude.[100] Having a youth bulge can be seen as one factor among many in explaining social unrest and uprisings in society.[101] Quantitative historian Peter Turchin noted intensifying competition among graduates, whose numbers were larger than what the economy could absorb, a phenomenon he termed elite overproduction, led to political polarization, social fragmentation, and even violence as many became disgruntled with their dim prospects despite having attained a high level of education. Income inequality, stagnating or declining real wages, and growing public debt were contributory factors. Turchin argued that having a youth bulge and massive young population with university degrees were the key reasons for the instability of the 1960s and 1970s and predicted that the 2020s would see the pattern repeat itself.[14]

Because the baby boomers were a huge demographic cohort, when they entered the workforce they took up all the jobs they could find, including those below their skill levels. As a result, wages were depressed and many households needed two streams of income in order to pay their bills.[20]

In China, even though the Central Government made plans for increasing the people's access to education, school attendance, including at the elementary level, dropped by 25 million due to the Great Famine, and another fifteen million due to the Cultural Revolution. Yet despite all this, by the mid-1970s almost all Chinese children went to elementary school (96%), up six times from the early 1950s. Although Chinese figures for the people deemed illiterate or semi-literate appeared high—a quarter of Chinese over twelve years of age fell into these categories in 1984—the peculiarities of the Chinese language made direct comparisons with other countries difficult.[88]

Ignoring the skepticism of his comrades, Chairman Mao introduced the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956-57 encouraging intellectuals and elites from the old era to share their thoughts freely with the slogan, "Let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred school of thoughts contend". Mao thought that his revolution had already transformed Chinese society for good. The result was an outburst of ideas deemed unacceptable by the CCP and above all, Mao himself, which fueled his distrust of intellectuals. Mao responded with the Cultural Revolution, which saw the intelligentsia being sent to the countryside for manual labor. Post-secondary education was almost completely abolished in mainland China. There existed only 48,000 university students in China in 1970, including 4,260 in the natural sciences and 90 in the social sciences, 23,000 technical school students in 1969, and 15,000 teachers in training in 1969. Data on post-graduate students was not available, presumably because there were no such students. China had a population of around 830 million in 1970.[88]

In China, the baby boomers grew up during the Cultural Revolution, when institutions of higher learning were closed. As a consequence, when China introduced some elements of capitalist reforms in the late 1970s, most of this cohort found itself at a severe disadvantage as people were unable to take the various jobs that became vacant.[15]

Cultural and sociopolitical identities

[edit]Popular culture

[edit]

The arrival of the television set made it possible for a family of modest means to be entertained in ways previously reserved for the wealthy.[19] Soap operas—characterized by melodramatic plots focused on interpersonal affairs and cheap production value—are a genre that was named after being sponsored by soap and detergent companies. They proved to be popular in the 1930s on radio and migrated to television in the 1950s. Again successful in the new broadcast environment, many of their viewers from the 1950s and 1960s grew old with them and introduced them to their children and grandchildren. In the United States, soap operas often dealt with the various social issues of the day, such as abortion, race relations, sexual politics, and inter-generational conflicts,[102] and they often took positions that were, by the standards of their day, progressive.[103] In Europe, and especially in the United Kingdom, the top soap operas typically featured working- or middle-class people, and most soap operas promoted post-war social-democratic values.[104]

Following the Second World War, the United States was not just a land of peace and prosperity but also of anxiety and fear, of cultural deviancy and ideological subversion. And one victim of said paranoia was comic books.[105] Comic books were blamed for the rise in juvenile delinquency in that country was blamed on comic books because a number juvenile offenders admitted to reading them.[106] This culminated in the book Seduction of the Innocent (1954) by Fredric Wertham,[106] causing a decline in the comics industry.[106] To address public concerns, in 1954 the Comics Code Authority was created to regulate and curb violence in comics, marking the start of a new era, the Silver Age of American comics, which lasted until the early 1970s.[107] Unlike those of the Golden Age, stories from the Silver Age moved away from horror, and crime.[108] Plots shifted towards romance and science fiction, deemed acceptable by the Code.[105] For a variety of stories and characters, scientific-sounding concepts replaced magic and gods.[109] Many plots were escapist fantasies and reflected the cultural zeitgeist of the day, featuring traditional family values (with an emphasis on gender roles and marriage) as well as gender equality.[110]

J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye (1951) attracted the attention of adolescent readers even though it was written for adults. The themes of adolescent angst and alienation in the novel have become synonymous with young-adult literature.[111] But according to Michael Cart, it was the 1960s that saw the maturing of novels for teenagers and young adults.[112] One early example of this genre was S. E. Hinton's The Outsiders (1967). The novel features a truer, darker side of adolescent life that was not often represented in works of fiction of the time.[113][114] Written during high school and written when Hinton was only 16,[115] The Outsiders also lacked the nostalgic tone common in books about adolescents written by adults.[116] The Outsiders remains one of the best-selling young-adult novels of all time.[116] Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret. (1970) by Judy Blume was another major success.[117][118] Blume was one of the first novelists who focused on such controversial topics as masturbation, menstruation, teen sex, birth control, and death.[119][120]

Cultural influences

[edit]

In the West, those born in the years before the actual boom were often the most influential people among boomers. Some of these people were musicians such as The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and The Rolling Stones; writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Betty Friedan, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Herbert Marcuse, and other authors of the Frankfurt School of Social Theory; and political leaders such as Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevara.[13][41][121][122] As romanticists and idealists safe from political retribution, radical youths did not care for competency or results as much as ideology. To this end, revolutionary icons such as Mao, Castro, or Guevara proved to be potent symbols.[121] Parents, by contrast, saw their influence greatly diminished. This was a time of rapid change, and what the parents could teach their children was less important than what the children knew and what their parents did not. For young people, life was vastly different from what their parents experienced during the interwar and war years. Economic depression, mass unemployment, war, and chaos were a distant memory; full employment and material comfort were the norm. Such a drastic difference in outlook and experience created a rift between the generations. As for the peers, they did have a significant influence on young people, for while the modus operandi of youth culture at the time was to be oneself and to disregard the opinions of others, in practice, peer pressure ensured conformity and uniformity, at least within a given subculture.[16]

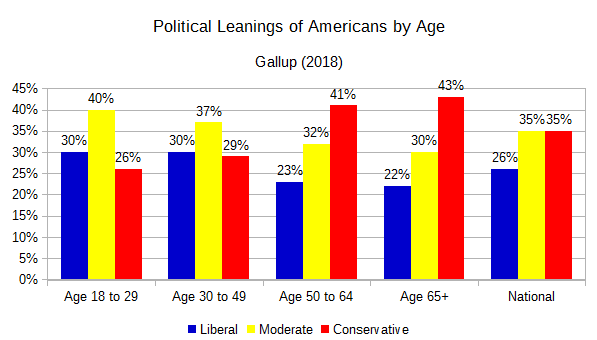

In the United States, the Baby Boomers lived through a period of dramatic cultural cleavage between the left-leaning proponents of change and the more conservative individuals. Analysts believe this cleavage has played out politically from the time of the Vietnam War to the present day,[124] to some extent defining the divided political landscape in the country.[125][126] Leading-edge boomers are often associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, the later years of the civil rights movement, and the "second-wave" feminist cause of the 1970s.[127][128] Conversely, many trended in moderate to conservative directions opposite to the counterculture, especially those making professional careers in the military (officer and enlisted), law enforcement, business, blue-collar trades, and Republican Party politics.[127][128] On the other hand, trailing-edge boomers (also known as Generation Jones) came of age in the "malaise era" of the 1970s with events such as the Watergate scandal, the 1973–1975 recession, the 1973 oil crisis, the United States Bicentennial (1976), and the Iranian hostage crisis (1979). Politically, early boomers in the United States tend to be Democrats, while later boomers tend to be Republicans.[129]

During the 1960s and 1970s, the music industry made a fortune selling rock records to people between the ages of fourteen and twenty-five. This era was home to many youthful stars—people like Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, or Janis Joplin—who had lifestyles that all but guaranteed their early deaths.[16][note 4]

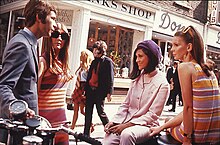

Across the Anglosphere, and increasingly in many other countries, middle- and upper-class youths started adopting the popular culture of the lower-classes, in stark contrast with previous generations. In the United Kingdom, for instance, young people from wealthy families changed their accents to approximate how working-class people spoke, and were not averse to the occasional use of profanities.[16] In France, the fashion industry discovered that trousers could outsell skirts in the mid-1960s.[16] Blue jeans, made popular by the likes of actor James Dean, steadily became a common sight across the Western world, even outside of college campuses.[16]

A remarkable characteristic of youth culture from this period is its internationalism. Whereas previous generations typically preferred cultural products from their own countries, those who came of age during the 1960s and 1970s readily consumed the music of other countries, above all the United States, the cultural hegemon of the era. English-language music was normally left untranslated. Musical styles from the Caribbean, Latin America, and later, Africa also proved popular.[16]

In Roman Catholic countries such as Ireland and Italy, the 1960s and 1970s saw a schism between the Church and the young on issues such as divorce or abortion. In the Canadian province of Quebec, religious attendance plummeted in the same period.[16]

In China, despite the passage of the National Marriage Law in 1950, which prohibited having concubines, allowed women to file for divorce, and banned arranged marriages, arranged marriages in fact remained common, and the notion of marrying for romantic love was considered a capitalist invention to be opposed during the period of the Cultural Revolution.[56]

Counterculture

[edit]

In the decades following the Second World War, cultural rebellion became a common feature in urbanized and industrialized societies, both East and West. In the context of the ideological competition of the Cold War, governments sought to improve the material standards of living of their own citizens but also to encourage them to seek meaning in their daily lives. However, young people felt a sense of alienation and sought to assert their own "individuality," "freedom," and "authenticity". By the early 1960s, elements of the counterculture had already entered public consciousness on both sides of the Atlantic, but were not yet viewed as a threat. But even then, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer acknowledged that the "most important problem of our epoch" was what many youths viewed as the empty materialism and superficiality of modern life. In the Soviet Union, the official youth periodical, Komsomol'skaia pravda, called for attention to the "psychology of contemporary young people". By 1968, counterculture was considered a serious threat. In the United States, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reported to the President that counterculture was a highly disruptive force not just in the nation but also abroad. In the CIA's view, it undermined societies East and West, from U.S. allies like West Germany, Japan, and South Korea to Communist nations like Poland, the Soviet Union, and China.[13] Long-time director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) J. Edgar Hoover suspected that students' protests and counterculture were instigated by Communist agents. However, the CIA subsequently found no evidence of foreign subversion.[130] Counterculture also affected Third World nations—those that chose to remain unaligned in the Cold War. In the Soviet Union, director of the Committee for State Security (KGB) Yuri Andropov became paranoid about the internal security. Under General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, the KGB amplified its efforts to suppress politically dissident voices, though the Soviet Union never quite returned to Joseph Stalin's style of governance.[13]

With hindsight, the CIA's assessments proved overly pessimistic. These youth movements had a bark that was worse than their bite. Despite sounding radical, the proponents of counterculture did not exactly demand the complete destruction of society in order to build it anew; they only wanted to work within the confines of the status quo to bring about the change they desired. Changes, if they came, were less well-organized than the activists themselves. Moreover, the loudest and most visible participants of counterculture often came from privileged background—with heretofore unheard-of access to higher education, material comfort, and leisure—which allowed them to feel secure enough in their activism. Counterculture was therefore not about material desires.[13][note 5]

Counterculture did, however, come with an entire pharmacopeia, including marijuana, amphetamines (such as "purple hearts"), and magic mushrooms. But perhaps the most notorious was a substance known as "acid" or lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Synthesized in 1938 by chemist Albert Hoffmann in his quest to cure migraine, its use as a psychedelic drug was promoted in the 1960s by psychologist Timothy Leary. Attempts to ban it in 1966 made the substance even more popular. A number of cultural icons of the late 1960s, such as poet Allen Ginsberg were known for using this drug.[130]

During the 1960s, conservative students objected to the counterculture and found ways to celebrate their conservative ideals by reading books such as J. Edgar Hoover's A Study of Communism, joining student organizations like the College Republicans, and organizing Greek events which reinforced gender norms.[131] While historians disagree over the influence of the countercultural movements of the 1960s in American politics and society, they tend to describe it in similar terms. For instance, sociologist Todd Gitlin calls it self-indulgent, childish, irrational, narcissistic, and even dangerous.[132] Moreover, it is possible that this movement did no more than creating new marketing segments for the specific sectors of the population, the "hip" crowd.[133][note 6]

Protests and riots

[edit]When they came of age during the late 1960s and 1970s, Baby Boomers immediately became politically active and made themselves heard due to the sheer size of their demographic cohort.[98] Violent crime and protests increased markedly in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many proponents of counterculture idealized violence and armed struggle against what they considered oppression, drawing inspiration from conflicts in the Third World and from the Cultural Revolution in Communist China, a creation of Mao Zedong intended to thoroughly sever the ties of society to its history, with deadly results. Some young men and women simply refused to engage in dialogue with mainstream society and instead believed that violence was a sign of their status as resistance fighters.[13] In May 1968, French youths launched massive protest demanding social and educational reforms, while labor unions simultaneously initiated a general strike, prompting countermeasures by the government. This led to a general mayhem in a manner similar to a civil war, especially in Paris. Finally, the government acquiesced to the demands of the students and workers; Charles de Gaulle stepped down as president in 1969.[134]

In the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), the 1950s was a period of strong economic growth and prosperity. But like so many other Western nations, it soon faced severe political polarization thanks to youth revolts. By the 1960s there was a general feeling of stagnation, which stimulated the creation of the primarily student-backed Extra-parliamentary Opposition (APO). One of the goals of the APO was reforms to the university system of admissions and registration. One of the most prominent APO activists was Rudi Dutschke, who declared "the long march through the institutions" in the context of recruitment for the civil service. Another major student movement of this era was the Red Army Faction (RAF), a militant Marxist group most active in the 1970s and the 1980s. Members of the RAF believed the West German economic and political systems to be inhumane and fascist; they looted stores, robbed banks, and kidnapped or assassinated West German businessmen, politicians, and judges. The RAF's reign of terror lasted until around 1993. It disbanded itself in 1998.[135] The RAF turned out to be deadlier than its American counterpart, the Weather Underground, which declared itself a "movement that fights, not just talks about fighting."[13]

Many West German youths in the late 1960s were suspicious of authority. Student demonstrators protested West Germany's rearmament, NATO membership, refusal to recognize the Democratic Republic of Germany (East Germany), and the role of the United States in the Vietnam War. On the other hand, the construction of the Berlin Wall (starting in August 1961, after the Berlin standoff) by East Germany boosted anti-communist sentiments in the West, where there was growing demands for high academic standards and opposition to communist indoctrination. A sort of civil war erupted in German academia. The Free University of Berlin was the heart of West German student movements. Many leading professors left because of the asphyxiating political atmosphere. However, by the mid-1970s, things calmed down. Students were more interested in academics and career preparation.[94] Indeed, counterculture had by this time invited stern public backlash. Resistance to change heightened. Major governments around the world implemented various policies intended to ensure "law and order".[13]

Some well-known slogans among youth rebels were, "When I think of revolution I want to make love," "I take my desires for reality and I believe in the reality of my desires," and "We want everything and we want it now!" These were evidently not what would normally be recognized as political slogans; rather, they were subjective expressions of the private individual.[16]

In general, though, no major government was overthrown by the protests and riots of the 1960s; indeed, governments proved rather stable during this turbulent period in history. Growing demands for change stimulated resistance to change.[13] Frustrated with the lack of revolutionary results despite their protests, which some skeptical observers such as Raymond Aron dismissed as no more than 'psychodrama' and 'street theater', some students became radicalized and opted for violence and even terrorism to achieve their goals. Nevertheless, other than publicity they achieved little. Doing one's "revolutionary service"—as the joke goes in Peru—did wonders for one's future career, though. From Latin America to France, students were aware that the civil service recruited university graduates and in fact, many had a successful career working for the government after leaving radical groups (and in some cases, becoming completely apolitical). Governments understood that people became less rebellious as they aged.[19]

In the United States, protests against American participation in the War in Vietnam shook college campuses and cities across the nation, even though the U.S. Armed Forces were deployed for similar (anti-communist) reasons they were during the Korean War, a conflict that provoked little political headwind. This was a time of growing focus on the self and mistrust of authority. Young people were no longer interested in military service the way their forebears were. Draft evasion grew, and many took to the streets to demand the abolition of conscription, which became a reality. Some of these student demonstrations grew violent, with fatal consequences.[98] Among counties that saw only peaceful demonstrations, the chances of the Democratic Party winning elections were unharmed. But in those that had riots, the Republican Party was able to attract new votes by appealing to the desire for security and stability. In fact, the backlash against the civil unrest of the late 1960s and early 1970s was so strong that even politicians in the 1990s like Bill Clinton had no choice but to endorse tough policies regarding public security in order to win elections.[136] High-profile protestors such as the hippies who confronted the police were the target of public hostility and condemnation.[137]

As a group, Western left-wing activists and radicals of the 1960s were intellectuals, and this was reflected in the ways their variants of political action and beliefs, primarily drawn from the experience in the classroom rather than on the factory floor. Many of these remained in academia and consequently became an unprecedentedly large cadre of cultural and political radicals on campus.[138]

One side effect of the student revolts of the late-1960s was that it made unions and workers realize they could demand more from their employers. Nevertheless, after so many years of full employment and growing wages and benefits, the working class was simply uninterested in starting a revolution.[19] To the contrary, some Americans even took to the streets to denounce counterculture and anti-war activists in the context of the War in Vietnam.[139]

In China, Chairman Mao in 1965 created the Red Guards, which initially consisted mainly of students, to purge dissident CCP officials and intellectuals in general, as part of the Cultural Revolution. The result was general mayhem. Mao eventually opted to deploy the People's Liberation Army against his own Red Guards to restore public order.[88] Mao disposed of millions of Red Guards by sending them to the countryside.[121]

Hippies and the Hippie Trail

[edit]The youthful proponents of counterculture, known as the hippies, disapproved of the modern world so much they sought refuge from it in communes and mystical religions. During the 1960s and 1970s, large groups of them could be found in any major European or American city. Male hippies wore long hair and grew beards, while female hippies eschewed anything that women traditionally wore to make themselves attractive, such as makeup and bras. Hippies were iconoclasts to varying degrees and rejected the traditional work ethic. They preferred love to money, feelings to facts, and natural things to manufactured items. They engaged in casual sex and used various hallucinogens. They were generally pacifists and pessimists. Many disliked politics and activism, though they were influenced by the political atmosphere of the time.[140] A significant cultural event of this era was the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, which drew huge crowds despite bad weather and a general lack of facilities.[140] Although it is commonly asserted that some half a million people attended, the actual figure is difficult to determine, even with aerial photography, as crowd experts would attest.[141]

The so-called Hippie Trail probably started in the mid-1950s, as expeditions of wealthy tourists and students traveling in small groups. They started from the United Kingdom, heading eastwards. As Western European economies grew, so did demand for international travel; many bus services sprang up to serve tourists. The first hippies—initially used to refer to men with long hair—joined the trail in the late 1960s. Many young people were beguiled by Eastern religions and mysticism, and they wanted to visit Asia to learn more. Others wanted to escape the conventional lifestyles of their home countries or saw opportunities for profit. Some smoked marijuana and wished to visit the Middle East and South Asia, where their favored products came from. But air travel was in its infancy at this time in history and was beyond the reach of most. For those seeking an adventure, traveling by long-distance bus and trains from Western Europe to Asia became an affordable alternative. But not all who traversed the Hippie Trail were from Europe. In fact, many hailed from Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Visas were easily obtained and in some cases were not required at all.[142] Many young and naive Western tourists fell victim to scammers, tricksters, and even murderers, taking advantage of the nascent global drug culture at the time.[143][144] The Hippie Trail ended in 1979 with the Iranian Revolution and the start of the Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989).[142]

Sexual revolution and feminism

[edit]In the United Kingdom, the Lady Chatterley trial (1959) and the first long-play of the Beatles, Please Please Me (1963) were to begin the process of altering public perception of human mating, a cause subsequently taken up by young people seeking personal liberation.[16][note 7]

In the United States, the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) in May 1960 approved the first contraceptive pill, a drug that has had a huge impact on the nation's history.[145] Invented by Gregory Pincus in 1956, the pill, as it is commonly called, marked the first time in human history when sexuality and reproduction can be reliably separated.[146] The pill and antibiotics capable of curing various venereal diseases eliminated two leading arguments against extra-marital sex, paving the way for the sexual revolution.[147] But the revolution did not happen right away; it was not until the 1980s that the pill become widely available in the United States and other Western nations.[146] In fact, the first wave of Baby Boomers married and had children early, following the footsteps of their parents.[10] Eventually, though, political attitudes towards human sexuality altered dramatically in the late 1960s because of young people. Although the behavior of most Americans did not change overnight, the heretofore mainstream beliefs on issues such as premarital sex, birth control, abortion, homosexuality, and pornography were openly challenged and no longer considered automatically valid. Individuals no longer feared social consequences when they expressed deviant ideas.[147] Indeed, the 1960s and 1970s were the most consequential in the history of human sexuality. While there was a backlash on moral or religious grounds, the sexual mores in Western societies were forever changed.[146] Nevertheless, there were concerns over possible abandonment or disrespect among (older) teenage girls and young women if they were to offer themselves to their boyfriends, a sentiment captured by the song "Will You Love Me Tomorrow?" from 1960.[98] Going steady—the practice of dating one person exclusively (as opposed to "playing the field")—rose in popularity among young Americans following the Second World War[148] and was part of mainstream youth culture through the 1980s, with teenagers beginning to go steady at progressively earlier ages.[149]

Sexologist Alfred C. Kinsey's books, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1958), employed confidential interviews to proclaim that sexual behaviors previously deemed unusual were more common than people thought. Despite triggering a storm of criticisms, the Kinsey Reports earned him the nickname the "Marx of the sexual revolution" due to their revolutionary influence. Many men and women celebrated their newfound freedom and had their satisfactions, but the sexual revolution also paved the way to new problems.[147] Many young people were under peer pressure to enter relationships they felt they were ill-prepared for, with serious psychological consequences. Illegitimate births ballooned, as did sexually transmitted diseases. Public health officials raised the alarm on an epidemic of gonorrhea and the emergence of the lethal acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Because many had strong opinions on various subjects relating to sexuality, the sexual revolution exacerbated sociopolitical stratification.[147]

Coupled with the sexual revolution was a new wave of feminism, as the relaxation of traditional views heightened women's awareness of what they might be able to change. Competition in the job market led many to demand equal pay for equal work and government-funded daycare services. Some groups, such as the National Organization for Women (NOW) equated women's rights with civil rights and copied the tactics of black activists, demanding an Equal Rights Amendment, changes to the divorce laws making them more favorable to women, and the legalization of abortion.[122]

In her book The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan discussed what she called "the problem that has no name"—namely, that married women with children were unhappy as housewives because "There is no other way for a woman to dream of creation or of the future. There is no way she can even dream about herself, except as her children’s mother, her husband’s wife."[150] "The personal is political" became the motto for the second wave of feminism.[123] But the feminist movement splintered, because some became radicalized and thought that groups such as NOW were not enough. Such radical feminists believed that people should start using gender-neutral language, marriage should be abolished, and that the traditional family unit was "a decadent, energy-absorbing, destructive, wasteful institution," rejected heterosexuality as a matter of principle, and attacked "not just capitalism, but men." At the other extreme, staunch social conservatives launched a major backlash, for example, by starting anti-abortion movements after the Supreme Court of the United States declared abortion constitutional in Roe v. Wade (1973). Yet despite their best efforts, mainstream American society changed. Many women entered the workforce, taking a variety of jobs and thus altered the balance of power between the sexes.[122]

Although the new feminist movement germinated in the United States in the 1960s, initially to address the concerns of middle-class women, thanks to the appearance of the word 'sex' in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was primarily intended to prohibit racial discrimination, it quickly spread to other Western nations in the 1970s and especially the 1980s. More women realized how much power they had as a group and they made use of it immediately, as can be seen in reforms regarding divorce and abortion laws in Italy, for example.[19]

Women flooded the workforce, and by the early 1980s, many sectors of the economy were feminized, though men continued to monopolize manual labor. Due to the law of supply and demand, such a surge in the number of workers diminished the prestige and income of those jobs. For many middle-class married women, joining the workforce made little economic sense, after accounting for all the extra costs, such as paid childcare and house work, but many chose to work anyway in order to achieve financial independence. But as the desire to send one's children to university became ever more common, middle-class women worked outside the home for the same reason their poorer counterparts did: making ends meet. Nevertheless, at least among middle-class intellectuals, men became much more reluctant to disrupt the careers of their wives, who were not as willing to follow their husbands wherever their jobs led them as was the case for previous generations.[19]

Although, in practice, the practitioners of feminism did not necessarily form an ideologically coherent group, they did succeed in creating a collective consciousness for women, something left-wing politicians in democracies were keen to acknowledge in order to court their votes. By the 1970s and 1980s, the traditional solidarity of the working class was fading away as different segments of this group began experience divergent economic prospects due to the continuation of industrial automation.[19]

Following the advent of a new atmosphere of sexual freedom, in the 1970s and 1980s, homosexuals were increasingly willing to demand acceptance by society and full legal rights.[146][147] It proved difficult to object to what consenting adults practiced in private.[147] Stating one's commitment to a heretofore prohibited or ostracized way of life, that is, 'coming out', was important to this movement. Homosexuality was decriminalized in England, Wales, and the United States in the late 1960s.[16] The world's first Gay Pride parade took place in 1969.[146] However, the HIV/AIDS epidemic acted as a brake on this social trend when its first victims were identified as such in the early 1980s. Writer Randy Shilts, himself a gay man, noted, "HIV is certainly character-building. It's made me see all the shallow things we cling to, like ego and vanity. Of course, I'd rather have a few more T-cells and a little less character."[151]

Marriage and family

[edit]

Marriage in many developed countries became much less stable in the 1980s, when Baby Boomers were getting married. In the West, this manifested in rising divorce rates. But this pattern was not seen East Asia.[16]: 323 Instead, the region saw declining marriage rates, particularly in Japan, where social changes led to the deterioration of Japanese men's social standing after World War II.[152] Men in East Asia were more likely to be unmarried than men in the West.[153]

Between 1970 and 1985, the number of divorces per thousand people doubled in Denmark and Norway and tripled in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. In England and Wales, while there was only one divorce per fifty-two weddings in 1938, that number became one every 2.2 fifty years later; this trend accelerated in the 1960s. During the 1970s, Californian women visiting their doctors showed a marked decline in the desire for marriage and children. In all Western nations, the number of single-person households steadily rose. In the major metropolitan areas, half the population lived alone. Meanwhile, the "traditional" nuclear family—a phrase first coined in 1924—was in decline. In Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and West Germany, only a minority of households consisted of two parents and their children by the 1980s, down from half or more than half in 1960. In Sweden, such a family unit fell from 37% to 25% in the same period; in fact, more than half of all children in Sweden in the mid-1980s were born to unmarried women.[16]

In the United States, what set the Boomers apart from their parents was not their marriage rates, or that they married in their early 20s, but rather that they were much more likely to be divorced. Divorced Boomers were less likely to remarry than their counterparts from the Silent Generation.[98] Statistically, marrying before the age of 25 increased the probability of divorce.[10] The nuclear family fell from 44% of all households in 1960 to 29% in 1980. But for African Americans, the figure was higher. In 1991, single mothers had given birth to the majority of children (70%) and headed a majority of households (58%).[16] As women's labor participation rose, rumors that career-oriented women were unhappy and unfulfilled or that mothers regretted returning to work began to spread. Mothers-in-law and medical doctors began urging women to forgo their ambitions in order to have children early to avoid problems infertility later on. Popular media frequently exhorted working women—if implicitly—to quit their jobs. Nevertheless, the share of American adults who rejected traditional gender roles steadily rose during the 1970s and 1980s.[98] As more and more women became financially independent, the traditional reason for women to marry faded away.[154] Marriage became increasingly viewed as an option, rather than an obligation.[98] In fact, since the 1960s, marriage has stopped being primarily focused on having and raising children but instead, the fulfillment of adults.[155] Married men were noticeably less willing to disrupt the careers of their wives.[16] Unmarried women were no longer deemed as "sick" or "immoral" the way they were in the 1950s. In addition, neither working mothers nor single parenthood (what used to be called illegitimacy) was socially ostracized the way they used to be.[98]

Parts of the reason why marriages were delayed or avoided were economic. People who entered the workforce during the 1970s and 1980s made less than their fathers did in the 1950s. Fertility rates fell as a result.[85] The rise in the number of cohabitating couples was also a factor. These couples claimed cohabitation helped them assess the suitability of a mate before marriage.[156]

In Italy, divorce was legalized in 1970 and confirmed by referendum in 1974. Abortion went through the same process in 1978 and 1981, respectively.[19] In the Canadian province of Quebec, the birth rate fell considerably during the 1960s and 1970s as the influence of the Catholic Church declined.[16]

While sociologists had known for a long time that humans tend to select mates of the same ethnicity, social class, personality traits, and educational level, a phenomenon known as assortative mating, during the 1970s and 1980s, an even stronger correlation between the educational levels of a married couple was observed in the United States. In fact, both the age at (first) marriage and the amount of time spent in school increased in the 1970s. Whereas in the past women had typically looked for men of high social status while men had not, by the late twentieth-century, men also looked for women of high earning potential, resulting in an even more pronounced educational and economic assortative mating. More generally, higher rates of university attendance and workforce participation by women affected the marital expectations of both sexes in that both men and women became more symmetrical in what they desired in a mate. The share of marriages in which both spouses were of the same educational level rose monotonically from 47% in 1960 to 53% by the mid- to late-1980s. Similarly, the share of marriages in which both spouses differ by at most one level of schooling increased from 83% in 1940 to 88% by the 1980s.[157]

Part of the reason why people increasingly married their socioeconomic and educational peers was economic in nature. Innovations that became commercially available in the late twentieth century such as the washing machine and frozen food reduced the amount of time people needed to spend on housework, which diminished the importance of domestic skills.[158] Moreover, it was no longer possible for a couple with one spouse having no more than a high-school diploma to earn about the national average; on the other hand, couples both of whom had at least a bachelor's degree could expect to make a significant amount above the national average. People thus had a clear economic incentive to seek out a mate with at least as high a level of education in order to maximize their potential income. A societal outcome of this was that as household gender equality improved because women had more choices, income inequality widened.[159]

In midlife

[edit]Economic power

[edit]By the early 2000s, the Baby Boomers reached middle age and were starting to save for retirement, though not necessarily enough. Seeking to increase their income and thus savings, many started investing, pushing interest rates to the floor. Borrowing became so cheap that some investors made rather risky decisions in order to get better returns. Financial analysts call this the "seeking yield" problem. But even the United States was not enough to absorb all these investments, so the capital flowed overseas, helping to fuel the considerable economic growth of various developing countries.[20] Steve Gillon has suggested that one thing that sets the Baby Boomers apart from other generational groups is the fact that "almost from the time they were conceived, boomers were dissected, analyzed, and pitched to by modern marketers, who reinforced a sense of generational distinctiveness".[160]

This is supported by the articles of the late 1940s identifying the increasing number of babies as an economic boom, such as a 1948 Newsweek article whose title proclaimed "Babies Mean Business",[161] or a 1948 Time magazine article called "Baby Boom".[162]

From 1979 to 2007, those receiving the highest one percentile of incomes saw their already large incomes increase by 278% while those in the middle at the 40th–60th percentiles saw a 35% increase. Since 1980, after the vast majority of Baby Boomer college goers graduated, the cost of college has been increased by over 600% (inflation-adjusted).[163]

After the CCP opened up their nation's economy in the late 1970s, because so many Baby Boomers did not have access to higher education, they were simply left behind as the Chinese economy grew enormously thanks to said reforms.[15]

Family values

[edit]

Among Americans aged 50 and up, the divorce rate per 1,000 married persons went from 5 in 1990 to 10 in 2015; that among those in the 65 and higher age group tripled to 6 per 1,000 during the same period. Marriage instability in early adulthood contributed to their high rate of divorce. For comparison, the divorce rate for that same period for people aged 25 to 39 went from 30 down to 24, and those aged 40 to 49 increased from 18 to 21 per 1,000 married persons.[164]