Man Ray

Man Ray | |

|---|---|

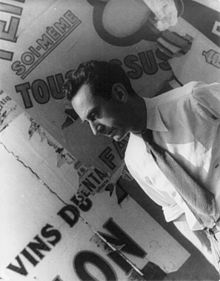

Man Ray, photographed at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Montparnasse exhibition in Paris by Carl Van Vechten on June 16, 1934 | |

| Born | Emmanuel Radnitzky August 27, 1890 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | November 18, 1976 (aged 86) Paris, France |

| Known for | Painting, photography, assemblage, collage, film |

| Movement | Dada, surrealism |

| Spouses | |

| Partner | Lee Miller (1929–1932) |

| Signature | |

Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky; August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976) was an American visual artist who spent most of his career in Paris. He was a significant contributor to the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal. He produced major works in a variety of media but considered himself a painter above all. He was best known for his pioneering photography, and was a renowned fashion and portrait photographer. He is also noted for his work with photograms, which he called "rayographs" in reference to himself.[1]

Biography

[edit]Background and early life

[edit]

During his career, Man Ray allowed few details of his early life or family background to be known to the public. He even refused to acknowledge that he ever had a name other than Man Ray,[2] and his 1963 autobiography Self-Portrait contains few dates.[3]

Man Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in South Philadelphia on August 27, 1890.[4][5] He was the eldest child of Russian Jewish immigrants[5] Melach "Max" Radnitzky, a tailor, and Manya "Minnie" Radnitzky (née Lourie or Luria).[6] He had a brother, Sam, and two sisters, Dorothy "Dora" and Essie (or Elsie),[6] the youngest born in 1897 shortly after they settled at 372 Debevoise St. in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.[5] In early 1912, the Radnitzky family changed their surname to Ray; Sam chose this surname in reaction to the antisemitism prevalent at the time. Emmanuel, who was nicknamed "Manny", changed his first name to Man and gradually began to use Man Ray as his name.[2][7]

Man Ray's father worked in a garment factory and ran a small tailoring business out of the family home. He enlisted his children to assist him from an early age. Man Ray's mother enjoyed designing the family's clothes and inventing patchwork items from scraps of fabric.[2] Man Ray wished to distance himself from his family background, but tailoring left an enduring mark on his art. Mannequins, flat irons, sewing machines, needles, pins, threads, swatches of fabric, and other items related to tailoring appear in much of his work,[8] and art historians have noted similarities between Ray's collage and painting techniques and styles used for tailoring.[7]

Mason Klein, curator of the exhibition Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention at the Jewish Museum in New York, suggests that Man Ray may have been "the first Jewish avant-garde artist."[5]

Man Ray was the uncle of the photographer Naomi Savage, who learned some of his techniques and incorporated them into her own work.[9]

First artistic endeavors

[edit]

Man Ray displayed artistic and mechanical abilities during childhood. His education at Brooklyn's Boys' High School from 1904 to 1909 provided him with solid grounding in drafting and other basic art techniques. While he attended school, he educated himself with frequent visits to local art museums. After his graduation, Ray was offered a scholarship to study architecture but chose to pursue a career as an artist. Man Ray's parents were disappointed by their son's decision to pursue art, but they agreed to rearrange the family's modest living quarters so that Ray's room could be his studio.[2] The artist remained in the family home over the next four years. During this time, he worked steadily towards becoming a professional painter. Man Ray earned money as a commercial artist and was a technical illustrator at several Manhattan companies.[2][7]

The surviving examples of his work from this period indicate that he attempted mostly paintings and drawings in 19th-century styles. He was already an avid admirer of contemporary avant-garde art, such as the European modernists he saw at Alfred Stieglitz's 291 gallery and works by the Ashcan School. However, he was not yet able to integrate these trends into much of his own work. The art classes he sporadically attended, including stints at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League, were of little apparent benefit to him. When he enrolled at the Ferrer Centre in the autumn of 1912, he began a period of intense and rapid artistic development.[7] The Centre, established and run by anarchists in memory of the executed Catalan anarchist educationalist Francisco Ferrer,[10] provided classes in drawing and lectures on art-criticism.[7] There Emma Goldman noted "a spirit of freedom in the art class which probably did not exist anywhere else in New York at that time."[7] Man Ray exhibited works in the Centre's 1912-13 group exhibition, with his painting A Study in Nudes reproduced in a review of the show in the Centre's associated magazine The Modern School.[7] This may have been Man Ray's first published art work, and the magazine would go on to print his first published poem (Travail) in 1913. During this period he also contributed illustrations to radical publications, including providing the cover-art for two 1914 issues of Emma Goldman's journal Mother Earth.[7]

Man Ray's work at this time was influenced by the avant-garde practices of European contemporary artists he was introduced to at the 1913 Armory Show. His early paintings display facets of cubism. After befriending Marcel Duchamp, who was interested in showing movement in static paintings, his works began to depict movement of the figures. An example is the repetitive positions of the dancer's skirts in The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows (1916).[12]

In 1915, Man Ray had his first solo show of paintings and drawings after taking up residence at an art colony in Grantwood, New Jersey.[13] His first proto-Dada object, an assemblage titled Self-Portrait, was exhibited the following year. He produced his first significant photographs in 1918, after initially picking up the camera to document his own artwork.[14]

Man Ray abandoned conventional painting to involve himself with the radical Dada movement. He published two Dadaist periodicals, that each only had one issue, The Ridgefield Gazook (1915) and TNT (1919), the latter co-edited by Adolf Wolff and Mitchell Dawson.[15][16] He started making objects and developed unique mechanical and photographic methods of making images. For the 1918 version of Rope Dancer, he combined a spray-gun technique with a pen drawing. Like Duchamp, he worked with readymades—ordinary objects that are selected and modified. His readymade The Gift (1921) is a flatiron with metal tacks attached to the bottom, and Enigma of Isidore Ducasse[17] is an unseen object (a sewing machine) wrapped in cloth and tied with cord. Aerograph (1919), another work from this period, was done with airbrush on glass.[18]

In 1920, Man Ray helped Duchamp make his Rotary Glass Plates, one of the earliest examples of kinetic art. It was composed of glass plates turned by a motor. That same year, Man Ray, Katherine Dreier, and Duchamp founded the Société Anonyme, an itinerant collection that was the first museum of modern art in the U.S. In 1941 the collection was donated to Yale University Art Gallery.[19]

Man Ray teamed up with Duchamp to publish one issue of New York Dada in 1920. For Man Ray, Dada's experimentation was no match for the wild and chaotic streets of New York.[20] He wrote that "Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is dada, and will not tolerate a rival."[20]

In 1913, Man Ray met his first wife, the Belgian poet Adon Lacroix (Donna Lecoeur) (1887–1975), in New York. They married in 1914, separated in 1919, and formally divorced in 1937.[21]

Paris

[edit]

In July 1921, Man Ray went to live and work in Paris, settling in the Montparnasse quarter favored by many artists. His accidental rediscovery of the cameraless photogram, which he called "rayographs", resulted in mysterious images hailed by Tristan Tzara as "pure Dada creations".[22]

Shortly after arriving in Paris, he met and fell in love with Alice Prin (popularly known as "Kiki de Montparnasse"), an artists' model and celebrated character in Paris bohemian circles. Prin was Man Ray's companion for most of the 1920s, and became the subject of some of his most famous photographic images. She also starred in his experimental films Le Retour à la raison and L'Étoile de mer.

In 1929, he began a love affair with the Surrealist photographer Lee Miller.[23][24][25] She was also his photographic assistant and, together,[26][27][28] they reinvented the photographic technique of solarization. Miller left him in 1932.

From late 1934 until August 1940, Man Ray was in a relationship with Adrienne Fidelin.[29][30] She was a Guadeloupean dancer and model and she appears in many of his photographs. When Ray fled the Nazi occupation in France, Adrienne chose to stay behind to care for her family.[31] Unlike the artist's other significant muses, Fidelin had until 2022 largely been written out of his life story.[32]

Man Ray was a pioneering photographer in Paris for two decades between the wars. Many significant members of the art world, such as Pablo Picasso, Tristan Tzara, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dalí, Peggy Guggenheim, Bridget Bate Tichenor,[33] Luisa Casati,[34] and Antonin Artaud, posed for his camera. His international fame as a portrait photographer is reflected in a series of photographs of Maharajah Yashwant Rao Holkar II and his wife Sanyogita Devi from their visit to Europe in 1927.[35][36] In the winter of 1933, surrealist artist Méret Oppenheim, known for her fur-covered teacup, posed nude for Man Ray in a well-known series of photographs depicting her standing next to a printing press.[37]

His practice of photographing African objects in the Paris collections of Paul Guillaume and Charles Ratton and others led to several iconic photographs, including Noire et blanche. As Man Ray scholar Wendy A. Grossman has illustrated, "no one was more influential in translating the vogue for African art into a Modernist photographic aesthetic than Man Ray."[38]

Man Ray was represented in the first Surrealist exhibition with Jean Arp, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Georges Malkine, André Masson, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso at the Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925. Important works from this time were a metronome with an eye, originally titled Object to Be Destroyed, and the Violon d'Ingres,[39] a stunning photograph of Kiki de Montparnasse,[40] styled after the painter/musician Ingres. Violon d'Ingres is a popular example of how Man Ray could juxtapose disparate elements in his photography to generate meaning.[41]

Man Ray directed a number of influential avant-garde short films, known as Cinéma Pur. He directed Le Retour à la Raison (2 mins, 1923); Emak-Bakia (16 mins, 1926); L'Étoile de Mer (15 mins, 1928); and Les Mystères du Château de Dé (27 mins, 1929). Man Ray also assisted Marcel Duchamp with the cinematography of his film Anemic Cinema (1926), and Ray personally manned the camera on Fernand Léger's Ballet Mécanique (1924). In René Clair's film Entr'acte (1924), Man Ray appeared in a brief scene playing chess with Duchamp.[42] Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia were all friends and collaborators, connected by their experimental, entertaining, and innovative art.[43][44]

Hollywood

[edit]The Second World War forced Man Ray to return to the United States. He lived in Los Angeles from 1940 to 1951, where he focused his creative energy on painting. A few days after arriving in Los Angeles, he met Juliet Browner, a first-generation American of Romanian-Jewish lineage. She was a trained dancer who studied dance with Martha Graham,[45] and an experienced artists' model. They married in 1946 in a double wedding with their friends Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. They were also close friends with Black Dahlia suspect George Hodel and his second wife Dorothy Harvey (also known as Dorero). George Hodel’s son Steve Hodel even proposes that the staging of the murder was an homage to Man Ray’s surrealist creations.[46] In 1948 Ray had a solo exhibition at the Copley Galleries in Beverly Hills, which brought together a wide array of work and featured his newly painted canvases of the Shakespearean Equations series.[47]

Later life

[edit]Man Ray returned to Paris in 1951, and settled with Juliet into a studio at 2 bis rue Férou near the Jardin du Luxembourg, where he continued his creative practice across mediums.[48] During the last quarter century of his life, he returned to a number of his iconic earlier works, recreating them in new form. He also directed the production of limited-edition replicas of several of his objects, working first with Marcel Zerbib and later Arturo Schwarz.[49]

In 1963, he published his autobiography, Self-Portrait (republished in 1999).[14]

Ray continued to work on new paintings, photographs, collages and art objects[50] until his death from a lung infection, in Paris, on November 18, 1976. He was interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Parisl[51] his epitaph reads "Unconcerned, but not indifferent". When Juliet died in 1991, she was interred in the same tomb. Her epitaph reads "Together again". Juliet organized a trust for Ray's work and donated much of his work to museums. Her plans to restore the studio as a public museum proved too expensive; such was the structure's disrepair. Most of its contents were stored at the Centre Pompidou museum.[45]

Innovations

[edit]Man Ray was responsible for several technical innovations in modern art, filmmaking, and photography. These included his use of photograms to produce surrealist images he called "Rayograms", and solarization (rediscovered with Lee Miller). His 1923 experimental film Le Retour à la raison was the first 'cine-rayograph', a motion picture made without the use of a camera.[52] Ray's 1935 Space Writing (Self-Portrait) was the first light painting, predating Picasso's 1949 light paintings, photographed by Gjon Mili, by fourteen years.[53]

Accolades

[edit]In 1974, Man Ray received the Royal Photographic Society's Progress Medal and Honorary Fellowship "in recognition of any invention, research, publication or other contribution which has resulted in an important advance in the scientific or technological development of photography or imaging in the widest sense."[54] In 1999, ARTnews magazine named Man Ray one of the 25 most influential artists of the 20th century. The publication cited his groundbreaking photography, "his explorations of film, painting, sculpture, collage, assemblage and prototypes of what would eventually be called performance art and conceptual art." ARTnews further stated that "Man Ray offered artists in all media an example of a creative intelligence that, in its 'pursuit of pleasure and liberty', unlocked every door it came to and walked freely where it would."[55][56]

Art market

[edit]Man Ray's Le Violon d'Ingres (1924), a famed photograph depicting a nude Alice Prin's back overlaid with a violin's f-holes, sold for $12.4 million on May 14, 2022, setting a new world record as the most expensive photograph ever to be sold at auction. The sale came after a drawn-out bidding period that lasted nearly ten minutes during Christie's New York's auction dedicated to Surrealist art.[57]

On November 9, 2017, Man Ray's Noire et Blanche (1926), formerly in the collection of Jacques Doucet, was purchased at Christie's Paris for €2,688,750 (US$3,120,658), becoming (at that time) the 14th most expensive photograph to ever sell at auction.[58][59][60] This was a record not only for Man Ray's work in the photographic medium but also for the sale at auction of any vintage photograph.[61]

Only two other works by Man Ray in any medium have commanded more at auction than the price captured by the 2017 sale of Noire et blanche. His 1916 canvas Promenade sold for $5,877,000 on November 6, 2013, at the Sotheby's New York Impressionist & Modern Art Sale.[62] And on November 13, 2017, his assemblage titled Catherine Barometer (1920), sold for $3,252,500 at Christie's in New York.[63]

Legacy

[edit]Self-Portrait was republished in 1999.[14]

In March 2013, Man Ray's photograph Noire et Blanche (1926) was featured in the US Postal Service's "Modern Art in America" series of stamps.[64]

-

Man Ray, 1920, Three Heads (Joseph Stella and Marcel Duchamp, painting bust portrait of Man Ray above Duchamp), gelatin silver print, 20.7 x 15.7 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

Salvador Dalí and Man Ray in Paris, on June 16, 1934, making "wild eyes" for photographer Carl Van Vechten

-

Man Ray, Paris, 1975, photographed by Lothar Wolleh

Selected publications

[edit]- Man Ray and Tristan Tzara (1922). Champs délicieux: album de photographies. Paris: [Société générale d'imprimerie et d'édition].

- Man Ray (1926). Revolving doors, 1916–1917: 10 planches. Paris: Éditions Surrealistes.

- Man Ray (1934). Man Ray: photographs, 1920–1934, Paris. Hartford, Connecticut: James Thrall Soby.

- Éluard, Paul, and Man Ray (1935). Facile. Paris: Éditions G.L.M.

- Man Ray and André Breton (1937). La photographie n'est pas l'art. Paris: Éditions G.L.M.

- Man Ray and Paul Éluard (1937). Les mains libres: dessins. Paris: Éditions Jeanne Bucher.

- Man Ray (1948). Alphabet for adults. Beverly Hills, California: Copley Galleries.

- Man Ray (1963). Self portrait. London: Andre Deutsch.

- Man Ray and L. Fritz Gruber (1963). Portraits. Gütersloh, Germany: Sigbert Mohn Verlag.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Rayograms by Man Ray". Time. April 18, 1932. Archived from the original on November 8, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Baldwin, Neil. Man Ray: American Artist; Da Capo Press; ISBN 0-306-81014-X (1988, 2000)

- ^ Rosenberg, Karen (November 19, 2009). "Mercurial Jester, Revealing and Concealing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ Warren, Lynne, ed. (November 15, 2005). "Man Ray". Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography. Vol. 2. Routledge. p. 1000. ISBN 9781135205362.

- ^ a b c d Herschthal, Eric (November 10, 2009), "Man Ray's Jewish Identity: 'Concealing And Revealing'", The Jewish Week, archived from the original on January 27, 2010,

Klein suggests that Ray may have even been the first Jewish avant-garde artist, though it is a tenuous claim given both the movement and Man Ray's disavowal of ethnic identity.

- ^ a b 1900 United States Federal Census

- ^ a b c d e f g h Francis Naumann, Conversion to Modernism: The Early Work of Man Ray. Rutgers University Press: ISBN 0-8135-3148-9 (2003).

- ^ Milly Heyd; "Man Ray/Emmanuel Rudnitsky: Who is Behind the Enigma of Isidore Ducasse?"; in Complex Identities: Jewish Consciousness and Modern Art; ed. Matthew Baigell and Milly Heyd; Rutgers University Press; ISBN 0-8135-2869-0 (2001).

- ^ Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (December 19, 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-63882-5.

- ^ Veysey, Laurence (1973). "The Ferrer Colony and Modern School". In: The Communal Experience: Anarchist and Mystical Counter-Cultures in America. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 77–177. ISBN 978-0-06-014501-9.

- ^ New York dada (magazine), Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, April, 1921, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou

- ^ "The Collection | Man Ray. The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows. 1916". MoMA. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ Staff. "Man Ray Is Dead in Paris at 86; Dadaist Painter and Photographer", The New York Times, November 19, 1976. Retrieved December 15, 2013. "His style changed in 1915 to 'reducing human figures to flat-patterned disarticulated forms.' He was living at the time in Ridgefield, N. J."

- ^ a b c Ray, Man (1999). Self Portrait: Man Ray (First paperback ed.). Bulfinch. ISBN 0-8212-2474-3.

- ^ Husar, Emma (2017). In the Spirit of Dada Man Ray, The Ridgefield Gazook, and TNT (Honors). University of Iowa. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "Inventory of the Mitchell Dawson Papers, 1810-1988". The Newberry. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "IMAGINE – The Israel Museum's searchable collections database". Imj.org.il. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ "Man Ray, Aerograph, 1919, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam". Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Cabanne, Pierre (July 21, 2009). Dialogues With Marcel Duchamp. Hachette Books. ISBN 9780786749713. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Man Ray – Prophet of the Avant-Garde | American Masters". PBS. September 17, 2005. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ Lacroix's first marriage had been to Adolf Wolff, an immigrant anarchist sculptor and poet, born in Brussels, Belgium.

- ^ "Untitled". The Art Institute of Chicago. 1923.

- ^ Shinkle, Eugénie, 1963-; ProQuest (Firm) (2008), Fashion as photograph : viewing and reviewing images of fashion, I.B. Tauris, pp. 71–72, ISBN 978-0-85771-255-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Charles Darwent (January 27, 2013). "Man crush: When Man Ray met Lee Miller". The Independent. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Giovanni, Janine D. "What's a Girl to Do When a Battle Lands in Her Lap?" New York Times Magazine Winter 2007: 68-71. ProQuest. March 2, 2017

- ^ Penrose, Roland. "Picnic [Nusch Éluard, Paul Éluard, Lee Miller, Unknown, Man Ray, Ady Fidelin]- 4771". LeeMiller.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Lee. "3697 - Nusch and Paul Ėluard, Roland Penrose, Man Ray and Ady Fidelin". LeeMiller.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Lee. "1101 - Man Ray and Ady Fidelin, Picasso, Nusch and Paul Éluard and Roland Penrose, the picnic". LeeMiller.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Yo, Adrienne, The New York Times, February 25, 2007, › 2007 › 02 › 25 › style › tmagazine › 25tmodel.html

- ^ Felder, Rachel, Overlooked No More: Ady Fidelin, Black Model 'Hidden in Plain Sight', The New York Times, May 2, 2022

- ^ Wendy A. Grossman and Sala E. Patterson, "Adrienne "Ady" Fidelin" in Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin American Biographies, ed. Franklin W. Knight and Henry Louis Gates Jr.; Oxford University Press, 2016.

- ^ Wendy A. Grossman and Sala E. Patterson, "Adrienne Fidelin" in Le Modèle Noire, Musée d'Orsay/Flammarion, 2019, p. 306-311. ISBN 978-2081480964

- ^ "Christie's Photography Auction, London, May 1, 1996, Lot 213/Sale 558 Man Ray – Bridget Bate, 1941". Christies.com. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ "[The Marquise Casati with Horses] (Getty Museum)". The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles.

- ^ Owens, Mitchell (August 2, 2019). "How Maharaja Yeshwant Holkar and Maharani Sanyogita Devi Turned Indore Into a Art Deco Paradise". Architectural Digest.

- ^ "Thoroughly Modern Maharaja: how an Indian prince amassed one of the world's greatest interwar design collections". www.theartnewspaper.com. September 18, 2019.

- ^ "Meret Oppenheim | Widewalls". www.widewalls.ch. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Grossman, Wendy (2009), Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens, University of Minnesota Press, p. 4, ISBN 978-0816670178

- ^ Getty collection. Retrieved November 6, 2009

- ^ Ray, Man (1963), Self Portrait, Little, Brown and Company, p. 158

- ^ Penrose, Roland. Man Ray. 1. Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975. Pg 92

- ^ "Entr'acte photo with Duchamp and Man Ray". Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Bors, Chris (January 9, 2008), "Winter Museum Preview: Top 5 London", Art+Auction, retrieved April 23, 2008

- ^ Neil Baldwin, Man Ray American Artist[permanent dead link]. Retrieved July 17, 2010

- ^ a b Flint, Peter B. (January 21, 1991). "Juliet Man Ray, 79, The Artist's Model And Muse, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ "Root of Evil" (Podcast). iHeart.

- ^ Andrew Strauss, "To Be Continued Unnoticed: Mathematics and Shakespeare in Hollywood," in Wendy A. Grossman, et al., Man Ray—Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare, Hatje Cantz, 2015

- ^ Neil Baldwin, Man Ray: American Artist, p. 278

- ^ Traub, Alex (July 23, 2021). "Arturo Schwarz, Refugee Who Became a Surrealism Tycoon, Dies at 97". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Man Ray". Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 38837-38838). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Foresta, M. (2003). "Man Ray". Grove Art Online.

- ^ "Man Ray | Space Writing (Self-Portrait) (1935) | Artsy". www.artsy.net.

- ^ "Progress Medal". Royal Photographic Society. 1974. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ Coleman, A. D. "Willful Provocateur"; ARTnews, May 1999.

- ^ Ray, Man (1998). "Plates" (Print book). In Weston Naef (ed.). Man Ray: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Christopher Hudson. p. 14. ISBN 0-89236-511-0. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ Angelica Villa, ARTnews, "Man Ray's Famed Photograph of Kiki de Montparnasse Sells for Record $12.4 M," May 14, 2022 [1]

- ^ Man Ray Makes a $3m Record in Paris, November 9, 2017, by Marion Maneker

- ^ Stripped Bare: Photographs from the Collection of Thomas Koerfer, Christie's Paris, November 9, 2017

- ^ Elodie Morel, 'My highlight of 2017' — Man Ray's Noire et Blanche, Christie's Paris, December 13, 2017

- ^ Wendy A. Grossman, "Surrealism and the Marketing of Man Ray's Photographs in America: The Medium, the Message, and the Tastemakers," in Networking Surrealism in the U.S.A. Agents, Artists and the Market, ed. Julia Drost, et al (DFK Paris/arthistoricum.net, 2019), 237. https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/arthistoricum/catalog/book/485

- ^ Wendy A. Grossman, "Surrealism and the Marketing of Man Ray's Photographs in America: The Medium, the Message, and the Tastemakers," in Networking Surrealism in the U.S.A. Agents, Artists and the Market, ed. Julia Drost, et al (DFK Paris/arthistoricum.net, 2019), 238, n.3

- ^ Man Ray, Catherine Barometer, $3,252,500 USD, Christie's New York, November 13, 2017

- ^ "U.S. Postal Service Dedicates Modern Art in America, 1913 — 1931 Forever Stamps". about.usps.com.

Sources

[edit]- Alexandrian, Sarane. Man Ray; J. P. O'Hara; ISBN 0-87955-603-X (1973).

- Allan, Kenneth R. "Metamorphosis in 391: A Cryptographic Collaboration by Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and Erik Satie" in Art History 34, No. 1 (February 2011): 102–125.

- Baldwin, Neil. Man Ray: American Artist; Da Capo Press; ISBN 0-306-81014-X (1988, 2000).

- Coleman, A. D. "Willful Provocateur"; ARTnews, May 1999.

- Foresta, Merry, et al. Perpetual Motif: The Art of Man Ray. Washington: National Museum of American Art; New York: Abbeville Press, 1988.

- Grossman, Wendy A., Adina Kamien-Kazhdan, Edouard Sebline, and Andrew Strauss. Man Ray—Human Equations: A Journey From Mathematics to Shakespeare; Hatje Cantz; ISBN 978-3775739207 (2015).

- Heyd, Milly. "Man Ray/Emmanuel Radnitsky: Who is Behind the Enigma of Isidore Ducasse?"; in Complex Identities: Jewish Consciousness and Modern Art; ed. Matthew Baigell and Milly Heyd; Rutgers University Press; ISBN 0-8135-2869-0 (2001).

- Klein, Mason. Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention; Yale University Press; ISBN 978-0300146837 (2009).

- Knowles, Kim, A Cinematic Artist: The Films of Man Ray. Bern; Oxford: Peter Lang; ISBN 9783039118847 (2009).

- Mileaf, Janine. "Between You and Me: Man Ray's Object to be Destroyed," Art Journal 63, No. 1 (Spring 2004): 4–23.

- Naumann, Francis. Conversion to Modernism: The Early Work of Man Ray; Rutgers University Press; ISBN 0-8135-3148-9 (2003).

External links

[edit]- Man Ray Trust Digital Photo Library[permanent dead link]. Searchable; over 1,000 photos

- Man Ray Trust

- Man Ray at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), Melbourne, Australia

- Man Ray at the Museum of Modern Art

- "Man Ray Laid Bare" from Tate Magazine

- Man Ray's Subtle Surrealistic Genius Women[permanent dead link]

- Works by or about Man Ray at the Internet Archive

- Works by Man Ray at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Collection of Man Ray short films

- Man Ray at IMDb

- Man Ray letters and album, 1922–1976. Research Library at the Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles

- Man Ray[permanent dead link] in the National Gallery of Australia's Kenneth Tyler collection

- Man Ray in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- Man Ray at The Jewish Museum

- Man Ray

- American contemporary painters

- 1890 births

- 1976 deaths

- American abstract painters

- Dada

- American collage artists

- American autobiographers

- American cinematographers

- American experimental filmmakers

- American male screenwriters

- American surrealist artists

- Surrealist filmmakers

- American expatriates in France

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Art Students League of New York alumni

- Artists from Philadelphia

- Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

- Jewish American screenwriters

- Jewish American artists

- People from Ridgefield, New Jersey

- Photographers from New York (state)

- American portrait photographers

- 20th-century American painters

- 20th-century American male artists

- American male painters

- 20th-century American photographers

- Boys High School (Brooklyn) alumni

- Film directors from New York City

- Film directors from New Jersey

- American male non-fiction writers

- Screenwriters from New York (state)

- Screenwriters from Pennsylvania

- Screenwriters from New Jersey

- People from Williamsburg, Brooklyn

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- Dadaists

- Assemblage artists

- 20th-century American artists

- Jews from Pennsylvania